Not Another Big Tech Stack

Anthropic's Jack Clark argues that regulation kills AI innovation, like nuclear rules before it. This is the wrong lesson.

Hi. If you are receiving this first edition of my Substack by email, we’ve interacted in the past. Please do let me know on mark [at] futureoflife.org if you’d rather not receive these. Also do let me know if you have any feedback or disagree with the below.

In a recent column, Anthropic’s Jack Clark warned against stringent AI rules, citing the history of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission and its chilling effect on reactor construction as an example. The nuclear regulator is now a recurring meme about the perils of regulation. But does this actually add up?

Early nuclear regulation

In the US, the construction of nuclear power plants started when Congress passed a law to lift a government monopoly on the technology and to make the widespread use of nuclear power a national goal. In those early days, regulation was put in the hands of the Atomic Energy Agency (AEC), which was given a dual mandate to promote and regulate nuclear energy. With the benefit of hindsight, this created an obvious conflict of interest at the heart of the regulator.

Many agency staff were not archetypical bureaucrats wanting to curb industry behaviour but instead worried that stringent regulation would cause the US to fall behind Great Britain and the U.S.S.R. - both of which were ahead at the time. In 1955, AEC Commissioner Willard Libby further worried that “this great benefit to mankind will be killed aborning by unnecessary regulation”.

Technical advances and a permissive regulatory environment spurred a boom in reactor building. Between 1965 and 1970, the licensing and inspection caseload grew by 600% and started to create backlogs. In the ensuing decade, President Reagan dissolved the AEC and established a new agency with a single, regulation-focussed mandate, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The President made this change to create a more streamlined body that would speed up licensing for new plants (not, as you might think, out of concern over its predecessor’s conflicted mandate!).

The Three Mile Island accident

In 1979, equipment malfunction and human errors led to a partial meltdown at a nuclear plant at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. Widespread uncertainty about the cause of the meltdown, how to deal with it, and conflicting information from experts undermined the credibility of the nuclear industry. In response, the regulator suspended all licenses for new nuclear reactors and imposed a host of new measures. Henceforth, safety-related systems were subjected to much more rigorous testing and plant operators had to be trained to a much higher standard.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s course correction came too late to save the industry. Authorities, concerned that a hydrogen bubble that had built up in the reactor might explode, ordered the evacuation of 144,000 people. Large swaths of the public came to reject nuclear technology, already tainted by its association with nuclear weapons, as a dominant source of energy.

The nuclear industry would beg for stringent regulation if it could go back in time and prevent the regulatory crackdown that followed Three Mile Island. The biggest blow to the industry was not overregulation stifling its development, but lax safety standards that failed to prevent accidents first at Three Mile island in the U.S. and, a few years later, at Chernobyl in the U.S.S.R.

Lessons for California today

The history of nuclear power regulation shows that proactive regulation can be required both for an industry to thrive and for society to reap the benefits. With better regulation in place from the outset, the U.S. might have embraced nuclear power as a game-changing source of renewable energy. The world’s biggest energy consumer could have decarbonised decades sooner, thereby securing energy independence from the Middle East and untold climate benefits.

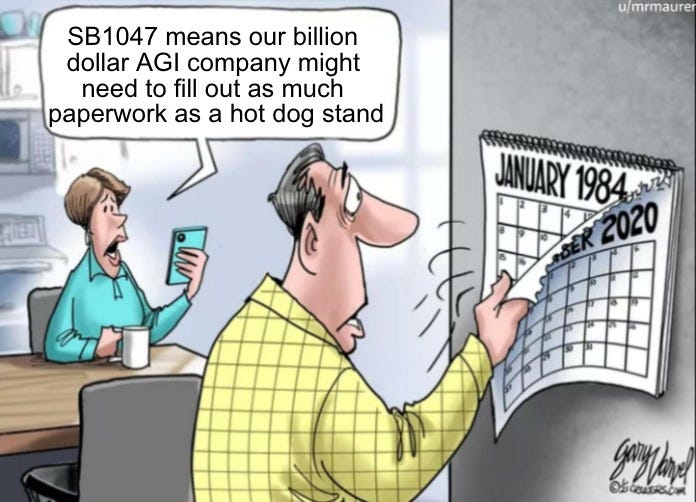

Last week, and much to my surprise, Anthropic pushed to water down SB1047, a landmark AI bill in California (lobbyist letter here). In clear parallels with the history of nuclear regulation, they push for the complete elimination of the proposed state regulator and suggest that enforcement should only happen after a catastrophe has occurred.

If successful, this seems like a move that the industry, and society at large, may come to regret. Society needs sensible regulation, like California’s SB1047, to prevent an AI equivalent of Three Mile Island from robbing us from the benefits that the technology can bring. Once public trust in AI is lost, it may be impossible to win it back.

Meme of the Month

Final note

I hope you enjoyed this first edition of my substack. Feedback is welcome through mark@futureoflife.org.

If you are looking to do some more summer reading, I can recommend:

My colleague Hamza’s piece in TIME magazine about the perils of using English exclusively for running all AI safety tests.

This worrying piece of analysis by Shakeel Hashim of the American Edge Project, which apparently uses Meta funding to pay for anti AI regulation ads.

Professor Yi Zeng announcing the Chinese AI Safety Network on LinkedIn, a promising step towards institutionalisation of AI Safety in China.

Reuters reporting on “Strawberry”, an innovation that OpenAI hopes will boost the reasoning capabilities of it’s next model.